Exposé: How Abdiweli Hassan Rose From Obscurity to Kenya’s Biggest Real Estate Player as Money Laundering Questions Swirl

Kenyan authorities are facing an uncomfortable question they have so far avoided.

How did Abdiweli Hassan, a man with no documented history of real estate development, suddenly command Sh65 billion for Kenya’s largest private property deal?

The question has become unavoidable as international investigations into massive fraud abroad increasingly point to Nairobi real estate, with Eastleigh named as a key destination for unexplained capital flows.

At the centre of that transformation stands Abdiweli Hassan.

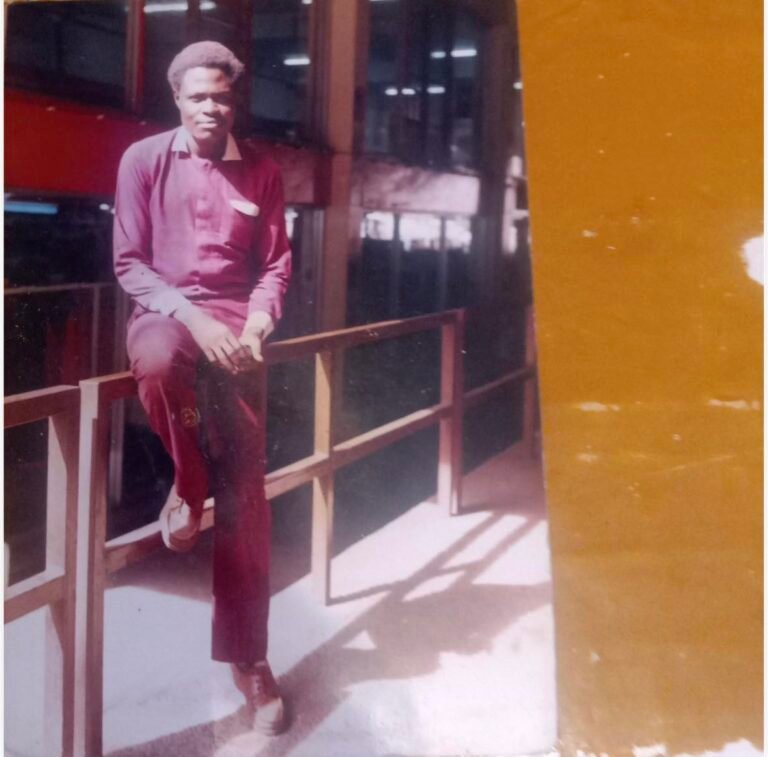

From Nowhere to Business Bay Square

Hassan’s public profile begins almost abruptly with Business Bay Square Mall, a massive commercial complex that reshaped Eastleigh’s skyline.

There is no visible trail of:

-

earlier developments

-

incremental growth projects

-

known financiers

-

institutional lending history

He did not climb the ladder.

He appeared at the top.

Within a short period, Hassan transitioned from an unknown figure to the face of one of Eastleigh’s largest commercial hubs, positioning himself as a serious real estate power broker.

The Eastleigh Factor

Eastleigh did not just grow fast.

It exploded.

High rise buildings appeared almost overnight.

Cash heavy businesses flourished.

Ownership structures became difficult to trace.

For investigators, Eastleigh represents the perfect environment for integrating illicit money into the formal economy:

-

dense cash circulation

-

informal financial networks

-

rapid construction normalising sudden wealth

-

limited scrutiny of capital sources

Business Bay Square sits at the heart of that ecosystem.

Minnesota Fraud Trail Meets Nairobi Property

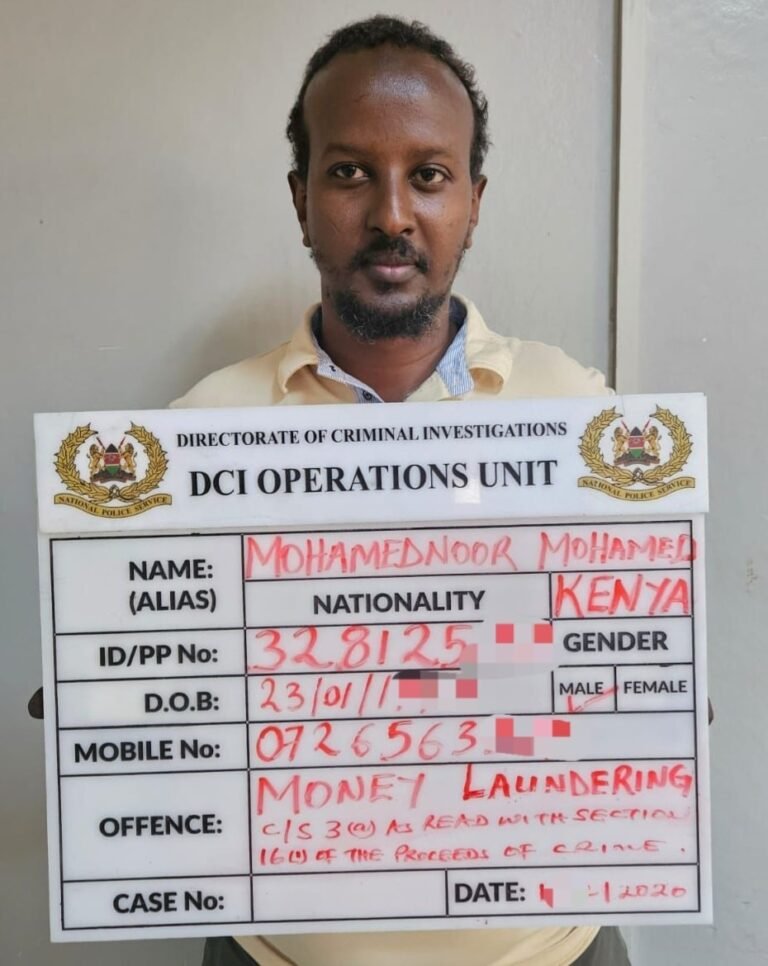

As global fraud investigations intensified, a disturbing pattern emerged.

Billions siphoned from public programs abroad were traced through complex laundering routes into Kenyan real estate.

Court records have already shown how foreign fraud proceeds were used to buy Nairobi apartments and stakes in property companies.

Named individuals were indicted for facilitating the movement of money into Kenya.

The direction of travel was clear.

Money out.

Property in.

And Eastleigh was repeatedly identified as ground zero.

The Sh65 Billion Leap to Tatu City

Then came the announcement that stunned even seasoned developers.

In October 2025, Abdiweli Hassan unveiled a Sh65 billion mega development at Tatu City, partnering with Rendeavour.

The scale was unprecedented.

Most developers spend decades building capacity to mobilise even a fraction of that capital.

Hassan leapt from a single mall to Kenya’s biggest private real estate deal in one move.

No financing breakdown was provided.

No investor list released.

No capital source disclosed.

Only vision statements.

The Legal Intimidation Pattern

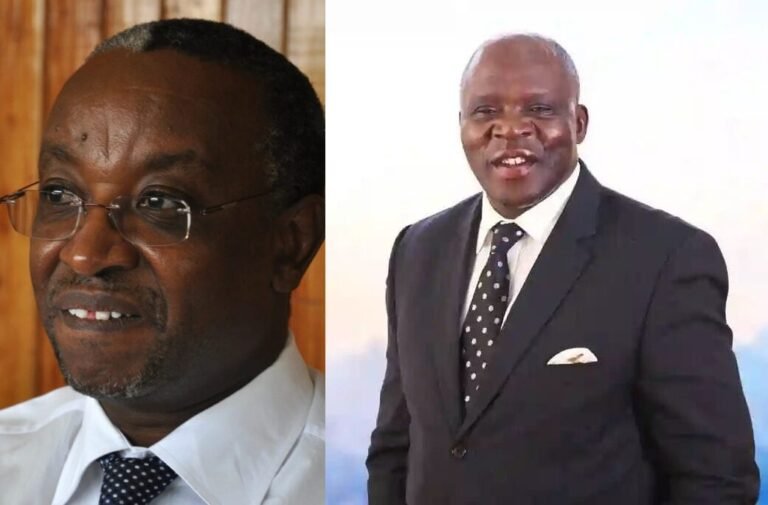

When Okiya Omtatah accused Hassan of operating at the centre of a rice import cartel undermining Kenyan farmers, Hassan did not respond with transparency.

Instead, his legal team, led by Ahmednasir Abdullahi, issued threats demanding retraction.

The response was telling.

The denial focused narrowly on rice quotas.

It avoided every other question:

-

Where did the capital come from

-

How was Business Bay Square financed

-

How is the Sh65 billion project funded

Omtatah refused to retreat, declaring that parliamentary privilege would not be silenced.

The confrontation dragged Hassan’s finances into national focus.

Shell Companies and Cartel Structures

The rice scandal exposed a familiar pattern.

Recently incorporated companies with no track record secured multi billion shilling government deals.

Ownership details were unclear.

Directors were unreachable.

Paper entities moved huge sums.

Omtatah alleged these companies were fronts.

Not operators.

Conduits.

He implied that Hassan operated above them, not as a visible bidder, but as a beneficiary within a cartel structure that uses procurement to move money.

Hassan denies this.

But denial is not documentation.

Why Tatu City Raises Red Flags

The Tatu City project offers conditions that investigators find attractive for laundering capital:

-

Special Economic Zone tax relief

-

reduced oversight

-

long construction timelines

-

phased development

-

massive future cash flows

Once operational, rents and sales generate legitimate income streams that permanently wash original capital.

If money laundering has an integration phase, this is what it looks like.

What Hassan Has Not Explained

If Hassan’s wealth is clean, answers would be simple.

Yet he has never publicly provided:

-

a documented business history before Business Bay Square

-

audited financial statements

-

proof of capital origin

-

names of equity partners

-

bank financing records

Instead, critics face legal threats.

Transparency repels suspicion.

Opacity attracts it.

What Investigators Are Already Showing

International prosecutors have already:

-

traced fraud money into Nairobi property

-

named Kenyan residents in laundering schemes

-

identified specific real estate purchases

-

mapped transfer routes

These cases show capability.

The only unanswered question is scale.

Kenya’s Real Test

This is no longer about Abdiweli Hassan alone.

It is about whether Kenya:

-

demands source of funds verification

-

enforces beneficial ownership disclosure

-

distinguishes investment from laundering

-

protects its real estate sector from becoming a global wash zone

Without scrutiny, the skyline becomes evidence.

The Sh65 Billion Question

Abdiweli Hassan now stands at a crossroads.

Either:

-

he is a visionary developer whose capital sources will eventually be proven legitimate

Or:

-

he represents the most successful integration of illicit funds into Kenyan real estate to date

Silence will not resolve that question.

The Sh65 billion did not come from nowhere.

And Kenya cannot keep pretending it did.