The deaths of Cyrus Jirongo and Jacob Juma continue to raise troubling questions that Kenya has never honestly confronted. Years apart, the two businessmen lived different lives but left behind a chilling trail of similarities that refuse to be dismissed as coincidence.

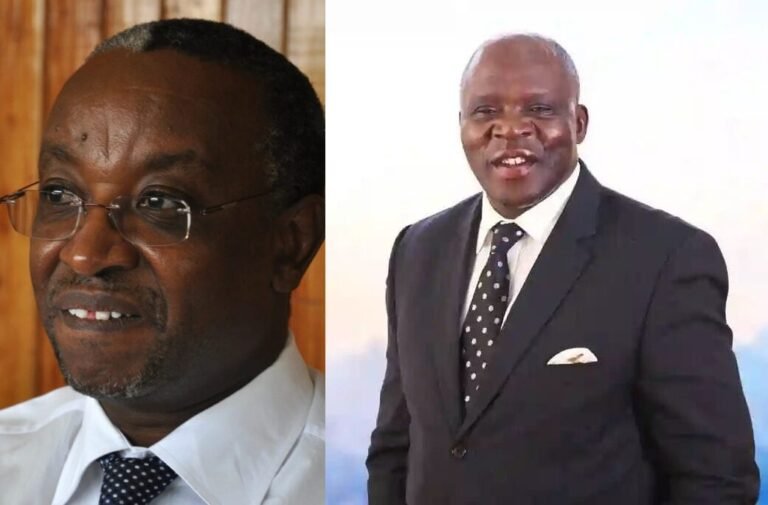

Both men were Luhyas from minority sub tribes. Jirongo hailed from the Abatiiriki while Juma came from the Batura. Their rise followed a familiar Kenyan path. They built wealth through government linked procurement. Jirongo mentored Juma. Their businesses were controversial at times, yet both emerged as powerful and influential figures.

That influence became dangerous the moment they fell out with the state.

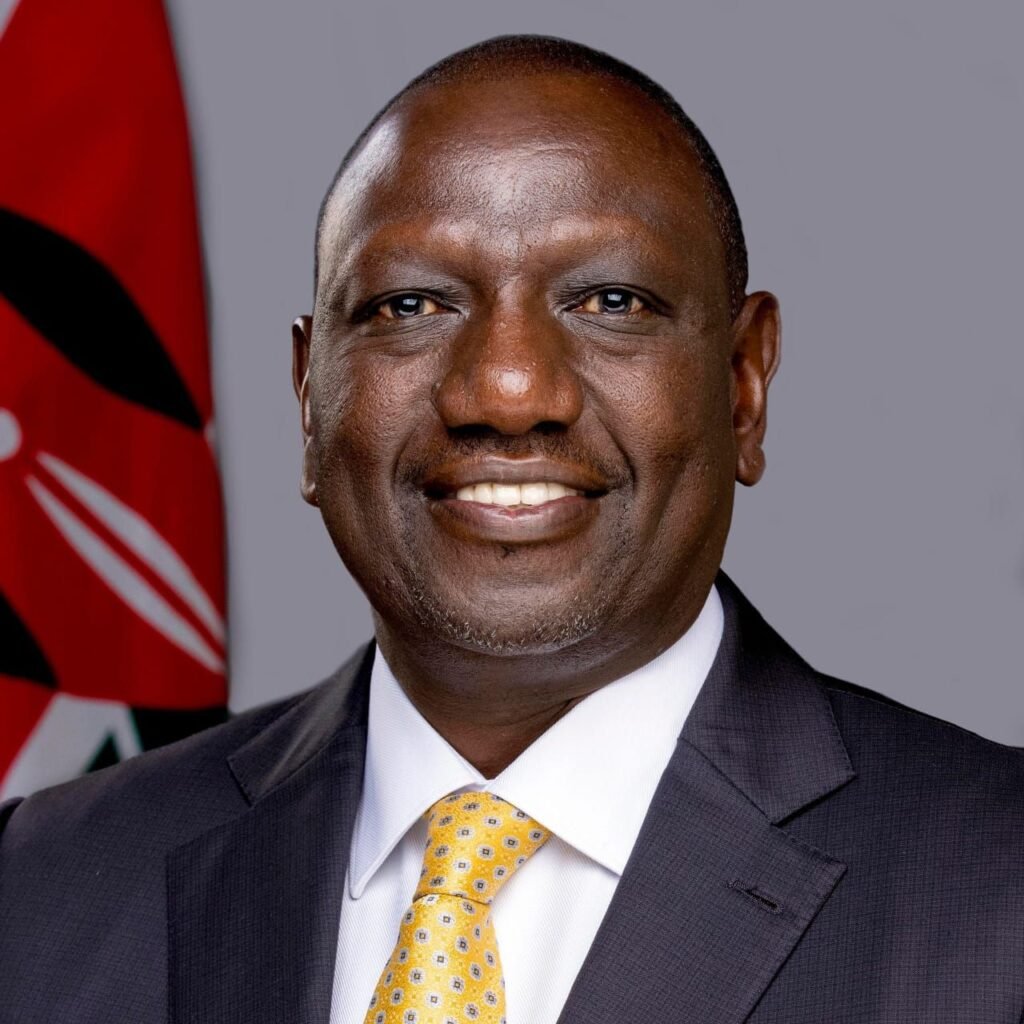

Juma turned into one of the loudest critics of the Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto administration, publicly accusing senior officials of corruption and naming names. Jirongo, once deeply embedded in power, broke ranks and went international. That move alone unsettled the establishment. An internationally connected political financier is every regime’s nightmare.

Both men spoke without fear.

Juma repeatedly warned that his life was in danger. He openly named William Ruto as a person he believed would be responsible for his assassination, even detailing meetings allegedly held to plan his elimination. Jirongo went further. At Juma’s burial in Mungore, he accused Ruto directly.

“William Ruto twisted his neck,” Jirongo said, warning Kenyans that Ruto was “accustomed to shedding blood.”

Years later, Jirongo himself would echo the same fear. In a public podcast conversation with Senator Edwin Sifuna, he claimed that releasing his information packed book would get him killed.

“I will be dead meat,” he said.

Both men were later found dead.

The circumstances surrounding their deaths deepen the unease. Both were driving Mercedes Benz vehicles. Both died at night. Independent theories suggest their times of death may have been similar. In both cases, investigators and witnesses questioned whether the men were killed at the scenes where their bodies were found.

In Juma’s case, residents near where his car was discovered in Karen said they heard no gunshots. Despite reports of bullets pumped into his body, there was no blood spatter consistent with such violence. Only a smear of blood was reportedly found on the co driver’s seat.

In Jirongo’s case, similar doubts emerged. Interim analyses suggested his body may have been placed in the vehicle’s pro box. Former MP Justus Khayanga Khaniri stated that Jirongo’s injuries did not match the level of damage on the vehicle. He noted that Jirongo’s face was clean, raising further questions about what really happened.

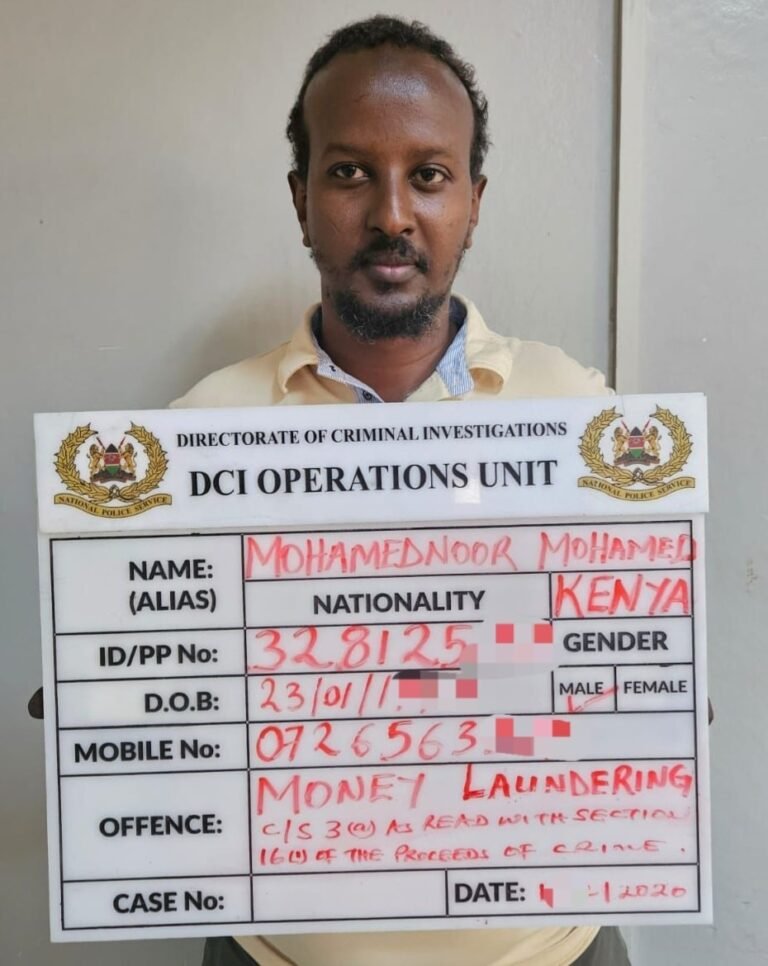

Then there is the matter of missing passengers.

In the Juma case, two unidentified individuals were reported to have gone to Karen Police Station to report the incident. Their identities were never clarified. In Jirongo’s case, CCTV footage allegedly showed two people inside his car shortly before the crash. Who they were remains unexplained.

Even in death, fear followed both men.

William Ruto did not attend either funeral. In Juma’s case, the absence spoke volumes. In Jirongo’s case, political manoeuvres followed. Kakamega Governor Fernandes Barasa organised a football event on the same day as Jirongo’s funeral, widely viewed as a face saving cover for the president’s absence.

The funerals themselves told different stories. Juma’s burial became a moment of public anger and protest. Jirongo’s funeral, critics argue, was diluted by leaders perceived as sympathisers of a government under suspicion. The atmosphere needed for hard questions and national outrage never fully formed.

What remains most disturbing is not just how Jirongo and Juma died, but what followed.

There has been no sustained fight for justice. Allies went quiet. Comrades retreated. Some were compromised. Others were intimidated. Silence replaced outrage.

This pattern mirrors darker chapters elsewhere. After the execution of Nigerian environmental activist Ken Saro Wiwa, dictator Sani Abacha dismissed criticism with chilling confidence.

“Even our detractors know that this administration is capable of taking tough decisions,” Abacha said.

Kenya today feels uncomfortably familiar.

The unresolved deaths of Cyrus Jirongo and Jacob Juma are not just about two men. They are about power, fear, and the cost of speaking too loudly in a system that has shown little tolerance for dissent.

The similarities are too many. The questions remain unanswered. And unless accountability becomes more than a slogan, Kenyans may yet witness more funerals that look disturbingly the same.

The warning signs are already there.